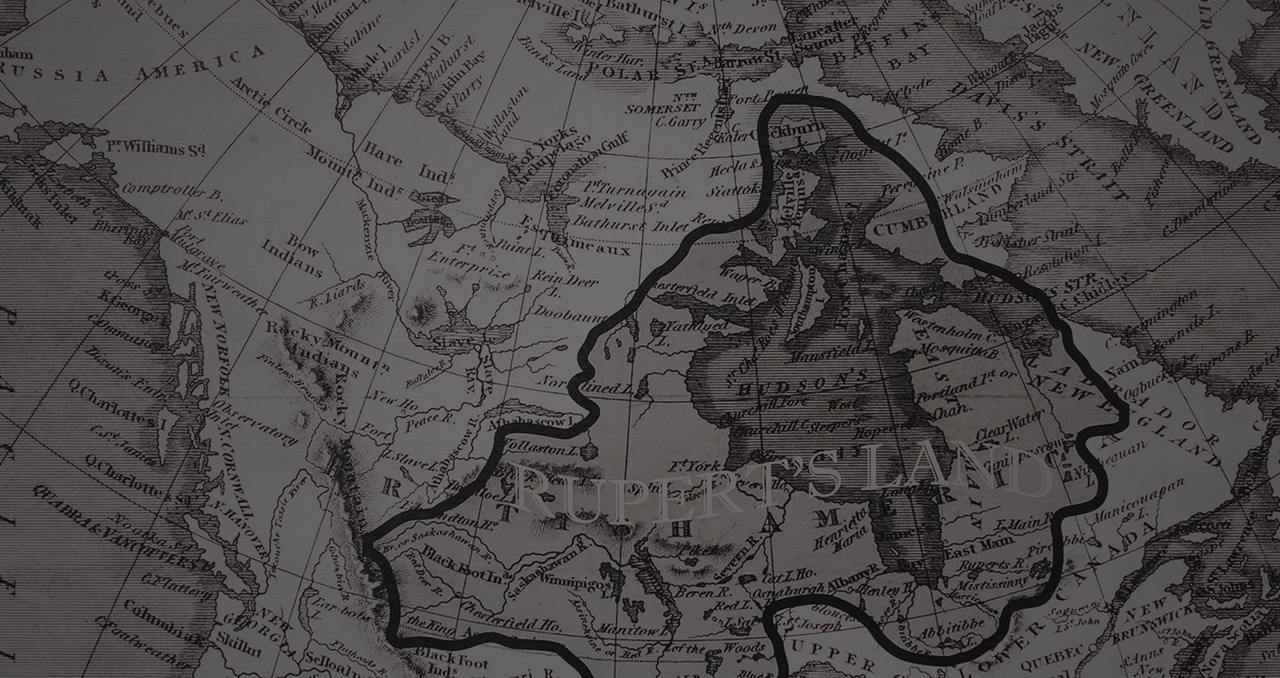

What is Rupert’s Land

In 1670, King Charles II of England granted a Charter to the Hudson’s Bay Company for:

“the sole trade and commerce of all those seas, streights, bays, rivers, lakes, creeks and sounds … and all mines royal … of gold, silver, gems and precious stones to be found, and that the said land be from henceforth called Rupert’s Land.”

The vast territory was named after Prince Rupert of Rhine, a cousin of Charles II, and the first appointed Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The Métis quickly became the intermediaries between trading partners; working as guides, interpreters, fur traders and provisioners to the new forts and trading companies.

Métis communities sprang up along the riverways from the Great Lakes to the Mackenzie Delta. The Rupert’s Land territory included all or parts of present-day Northwest-Nunavut Territory, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia.

Many parts of what was once known as Rupert’s Land became known to the Métis as the “Métis Homeland.”

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE MÉTIS NATION

Learn more about the Métis Nation with the Rupertsland Institute’s free, online resource: Métis Foundational Knowledge Themes.

Métis educators, Nation leaders, and cultural experts collectively agreed on the five themes to support educators as they develop their foundational knowledge about the Métis in Alberta.

Each theme shares information about Métis history, identity, and life in Alberta. Métis voices are authentically shared through the themes, woven together with academic research to best share the Métis story in Alberta.

What is the Métis Homeland?

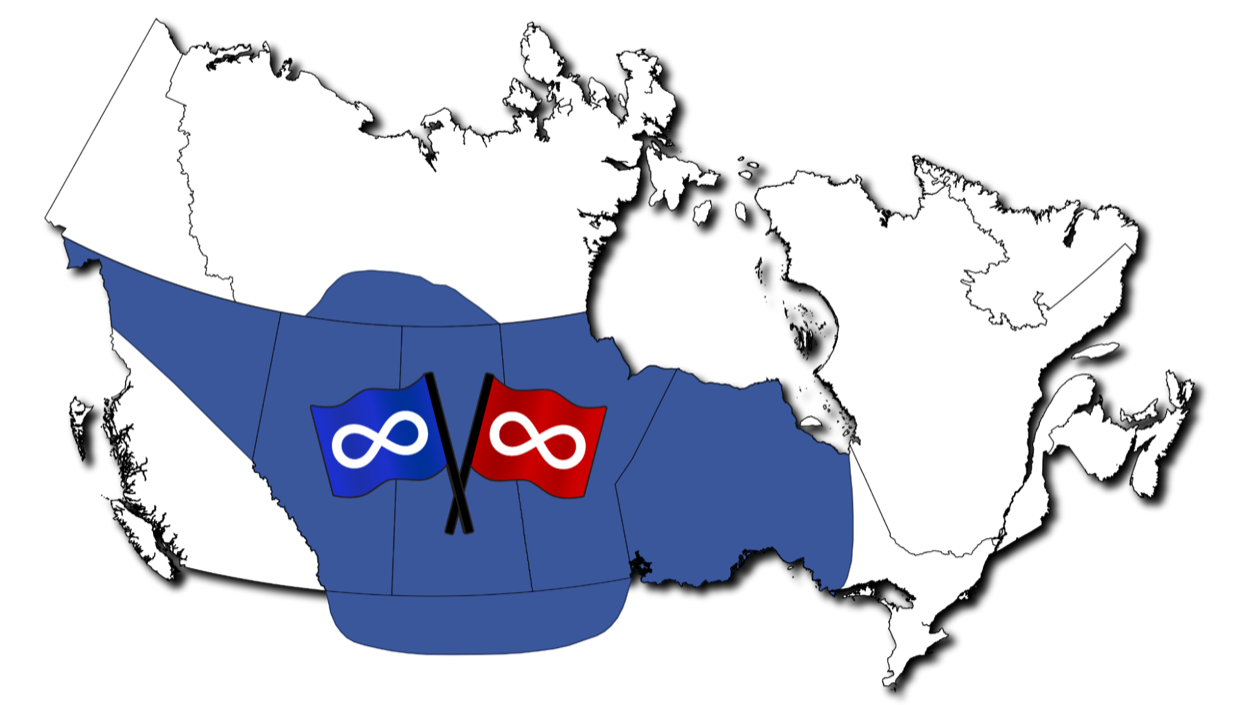

The Métis Nation has a generational Homeland that includes much of present-day Western Canada and northern sections of the United States. The specific areas include what is today: parts of southern Northwest Territories; parts of Ontario; Manitoba; Saskatchewan; Alberta; parts of British Columbia; parts of northern Montana; parts of North Dakota; and parts of Minnesota, USA. Métis ancestry, history, culture, and languages are rooted in these lands.

Métis Nation Homeland in Canada. Photo courtesy of the Métis Nation of Alberta, 2021.

WHO ARE THE MÉTIS?

Métis are a strong Indigenous people who celebrate distinct kinship, traditions, languages, culture, politics, governance, and history. Métis are a collective of communities with a common sense of origin and destiny with kinship networks that span a historic homeland. We share a common Métis nationalism distinct from other local identities.

Métis Ethnogenesis

Métis history begins with an ethnogenesis (or emergence) as a people and a Nation with a distinct ethnicity. Métis ethnicity has historical and ancestral connections to both First Nations and European relations. The unions between these two communities formed the first roots towards Métis nationhood. As communities of Métis people developed unique ways of being, doing, and knowing for themselves, they came together as a Métis Nation.

Understanding ethnogenesis as the origin of the Métis serves to counter the idea that Métis inherently means “mixed.” It is important that Métis identity is not reduced to mixedness.

Métis ethnogenesis acknowledges the beginnings of First Nations and European ancestors coming together, as well as that, by the mid-1700s, the Métis had already developed into a distinct community with their own culture, traditions, and language.

Today, Métis celebrate not just their historical roots and ethnogenesis, but also their distinct history, thriving peoplehood and vibrant culture. Rupertsland Centre for Teaching and Learning’s (RCTL) Foundational Knowledge Resources invites educators to understand and celebrate Métis spirit, history, and culture, and their resilience as a people and a Nation.

The National Definition of Métis

In September 2002, the Métis National Council adopted the following definition of Métis:

“Métis” means a person who self-identifies as Métis, is distinct from other Aboriginal peoples, is of historic Métis Nation ancestry, and is accepted by the Métis Nation.

- “Historic Métis Nation” means the Indigenous people then known as Métis who resided in the Historic Métis Nation Homeland.

- “Historic Métis Nation Homeland” means the area of land in west central North America used and occupied as the traditional territory of the Métis (or Half-breeds as they were then known).

- “Métis Nation” means the Indigenous people descended from the Historic Métis Nation which is now comprised of all Métis Nation citizens and is one of the “Aboriginal peoples of Canada” within the meaning of s.35 of the Constitution Act 1982.

- “Distinct from other Aboriginal peoples” means distinct for cultural and nationhood purposes.